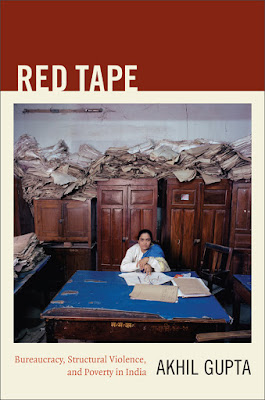

Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India by Akhil Gupta| A review by Parnika Praleya

Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India by Akhil Gupta, 2012, Duke University Press, ISBN: 9780822351108, 0822351102, Pages: 368.

Reviewed by: Parnika Praleya, University of Chicago

Akhil Gupta's

engaging book begins with the puzzle of - a high number of deaths due to

poverty in India not being viewed as a crisis despite the inclusion of the poor

in national sovereignty and democratic politics. Gupta is intrigued by the

invisibility of such violence in the public domain. Why are these deaths not

viewed as a crisis? What makes this violence invisible? What is the reason

behind this seeming apathy despite the state deriving legitimacy from bettering

lives of the poor? To answer these questions, Red Tape builds on Gupta's

earlier work dealing with themes of development, agrarian transformation, state

practice, globalization, and environmental history. Gupta's penchant for

approaching these "economic" issues through an anthropological lens

offer not only new theories for thinking about them but also juxtapose

questions of postcolonial development with politics and governance.

Gupta's compelling

theory of "structural violence" borrows from Galtung's and Paul Farmer's

work. Gupta argues that violence against the poor is enacted through the

everyday practices of bureaucracies (p. 33). Bureaucratic action systematically

produces arbitrary outcomes in its provision of care, actively condemning the

poor to death through state policy, deaths which were preventable (p. 6). Gupta's

detailed theoretical framework to support his argument makes the book engaging.

The painstaking development of the concept of "structural violence", of

why these deaths are more than just thanatopolitics (letting die), the move

away from the reified state to understand the production of arbitrariness make

the theoretical sections of this book compelling. Rather than being another

book utilizing Foucault and Agamben's concepts, Gupta builds upon their

framework in intelligent ways.

To look at

the everyday practices of bureaucracy, Gupta rejects Foucault's and Agamben's reified

state in which the disciplinary power is inherently rational and organized. The

first two chapters of the book build on Western theories of bare life,

biopolitics and governmentality and interrogate their relevance to a

postcolonial context. In doing so, there is a refreshing shift away from

viewing developing countries in general, and India in particular, at an earlier

stage of development, with Western developed nations as their telos of

development and modernity. While he uses Foucault to argue the normalization of

high deaths due to poverty as a statistical fact, he also underscores the

undertheorized nature of violence implicit in biopower. Biopower understood

through a managerial focus does not explain why some people get killed, and

others don't (p. 16). With examples from his, fieldwork Gupta shows the

inefficiencies of Census data collection, questioning the statistical

underpinning of the biopolitical project. Additionally, he argues that the poor

are homo sacer, where they can be killed without sacrifice, without a

state of exception (unlike Agamben's argument).

The rigorous

theoretical intervention is supported through an ethnographically thick

argument that connects bureaucratic actions to the arbitrariness of outcomes.

To investigate how ethics and politics of care are arbitrary and this

arbitrariness is systematically produced, Gupta considers three themes of

interaction between bureaucracy and the poor: corruption (chapters 3 and 4),

inscription (chapters 5 and 6) and governmentality (chapter 7). The rich

ethnographic vignettes of corruption are replete with Gupta's subtle

interpretations in conversation with people which add depth to his ethnographic

work. For example, his astute interpretation of the body language, spatial

arrangement and tone of conversation in the action of two patwaris (p. 84 -85)

is evidence of ethnographic work of high calibre. His investigation of the role

of narrative in the cultural construction of the state and the normalization of

corruption focuses on looking at newspapers and comparison of the representation

of the state in a popular novel and a well-known ethnography of India. By

astutely utilizing quasi-ethnographic sources like popular novels, Gupta

provides a diverse ethnographic understanding of how poor people's understanding

of the state is shaped by representations of corruption and circulation of

discourses about corruption.

The

investigation of the political consequence of bureaucratic insistence on

writing in a context of widespread illiteracy is a fascinating way of looking

at structural violence and production of arbitrariness. Moving away from the

assumption that writing is functional, Gupta argues that the state is

constituted through bureaucratic writing. The poor show agency in dealing with

this situation by counterfeiting documents, educating their children and

through political connections. His argument would have been bolstered if he

would have grappled with Chatterjee's (2004) "political society" in

some depth. Chatterjee's thesis on the community-based modality of claims

making by political society seemed to be an explanation for the phenomena being

observed (how the poor were engaging with political mobilization to get around

bureaucratic hurdles, the Bharatiya Kisan Union being a case in point).

The

investigation of the political consequence of bureaucratic insistence on writing

in a context of widespread illiteracy is a fascinating way of looking at

structural violence and production of arbitrariness. Moving away from the

assumption that writing is functional, Gupta argues that the state is

constituted through bureaucratic writing. The poor show agency in dealing with

this situation by counterfeiting documents, educating their children, and

making political connections. His argument would have been bolstered if he

would have grappled with Chatterjee's (2004) "political society" in

some depth. Chatterjee's thesis on the community-based modality of claims

making by political society seemed to be an explanation for the phenomena being

observed (the manner in which the poor were engaging with political

mobilization to get around bureaucratic hurdles, the Bharatiya Kisan Union

being a case in point).

These minor

points notwithstanding, Gupta's engaging local level ethnography into everyday

bureaucratic procedures of a disaggregated state perpetrating violence is

particularly pertinent during the pandemic. The Indian state's approach to the

pandemic was a draconian nation-wide lockdown announced with four hours' notice.

What unfolded was a spectacle of misery, with migrant workers left to fend for

themselves. Gupta's analysis of unintended outcomes by showing how they are

systematically produced by the friction between agendas, bureaus, levels, and

spaces that make up the state (p. 47) helps make sense of what has been called

the "migrant crisis" and the Indian government's handling of the

pandemic by controlling narratives, normalizing infections and deaths through

statistics, and its healthcare and policing hamstrung by their daily

processes.

Bibliography

Chatterjee, Partha. The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (Volumes 1, 2 & 3). Trans. Hoare, Quinton and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers, 2005 (1971).

Scott, James. Seeing Like a State: How Certain

Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1998.

***

Parnika Praleya is currently a graduate student at the University of

Chicago. Her research interests lie in institutions and contentious politics

and her research focuses on structural determinants of media polarization in

parliamentary democracies and looking at the impact of war-time social

movements in civil war-affected regions. When not researching, she can be found

reading Wodehouse, dabbling in photography, and traveling. Her blog, Maverick

Feet (https://maverickfeet.wordpress.com ),

is a reflection of all that she is.

Comments

Post a Comment