- Nabajyoti Saikia

|

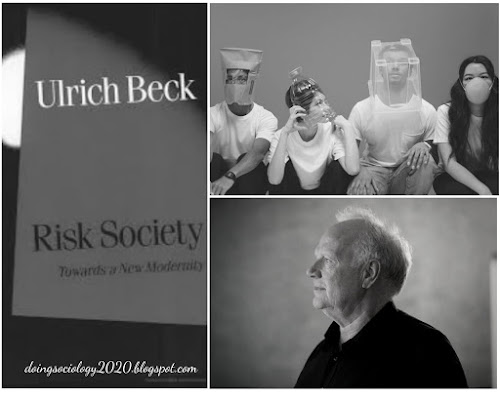

| Image source: Photo by cottonbro from Pexels |

The COVID-19 crisis, which began in Wuhan in the Hubei province of China has changed everyone’s lives across the globe. There is fear, uncertainty, and above all the pressing nature of the risk that each one of us faces as we carry out our everyday lives. People are falling sick; they are dying.

To understand what is happening around us, it is useful to consider German sociologist Ulrich Beck’s notion of ‘risk society’. Ulrich Beck was one of the first sociologists to recognise this strange paradox in late modern society; that risk might be increasing due to technology, science, and industrialism rather than being abated by scientific and technological progress. Rather than a world less prone to risk, late modernity might be creating what Beck famously described as a ‘world risk society’.[i]

At one level, Beck’s analysis is completely on track. According to him, these modern risks are characterized by three features; de-localization (its causes and consequences are not restricted to one geographical location), incalculableness (its consequences are in principle incalculable), and non-compensatibility (Not only is prevention taking precedence overcompensation, but we are also trying to anticipate and prevent risks whose existence has not been proven). All these three features are seen in the ongoing pandemic.

At another level, his analysis essentially stemmed from his experience in Germany and West Europe at a particular juncture of time and what he felt about the modernist project may not be entirely true for societies whose tryst with modernity was historically different; often colonially mediated. For Beck, much of the early modernist project was complete. Humankind he felt was no longer concerned exclusively with making nature useful, or with releasing mankind from traditional constraints. Genuine material needs had been reduced through the development of human and technological productivity, as well as through legal and welfare state protections and regulations. Hunger, shelter, and basic needs were largely met.

Beck in his book, Risk society: Towards a New Modernity (1992) has argued that ‘just as modernization dissolved the structure of feudal society in the nineteenth century and produced the industrial society, modernization today is dissolving industrial society and another modernity is coming into being’.[ii]

According to him, unlike the first modernity, which was characterized by the welfare state, full employment, collective lifestyles, and careless exploitation of nature, this new second modernity is characterized by large-scale ecological crises, general insecurity, individualization, and the decline in paid employment. In the first modernity, science and technology were seen as positive forces for social progress, whereas in second or advanced modernity, they are seen as the causes of modern risks rather than solutions.

For many of us reading in societies where welfare measures were barely there, Beck’s observations seem overstretched. Indeed the tragic plight of the migrants in India during the Lockdown reflects deep inequalities and differential state response in contrast to Beck’s description of modernity where the basic human needs have all been met; where there is near full employment and collective lifestyles.

Beck contended that ‘modern society has become a risk society in the sense that it is increasingly occupied with debating, preventing and managing risks that it has produced’.[iii] Further often this leads to a greater focus on security and control. The irony of the situation he writes, is the control is over something that one many not entirely know:

The crucial point, however, is not only the discovery of the unknown unknowns but that simultaneously the knowledge, control and security claim of state and society were, indeed had to be, renewed, deepened and expanded … in the face of the production of insuperable manufactured uncertainties society more than ever relies and insists on security and control…[iv]

Beck distinguishes between risk and hazard. Hazard refers to those naturally occurring events that are not the product of human activities, such as earthquakes. The history of human society has been the history of attempting to overcome, or, at the very least, minimise the impact of hazards. In contrast, for Beck, risks arise from the actions and activities of individuals and society through conscious decision- making. Specifically, Beck sees the generation of risk as indelibly connected with the rise of industrial society. Risks, he claims, presume industrial, i.e., techno-economic decisions and considerations of utility.

Beck further contends that widespread risks contain a 'boomerang effect', in that individuals producing risks will also be exposed to them. This argument suggests that wealthy individuals whose capital is largely responsible for creating pollution will also have to suffer when, for example, the contaminants seep into the water supply. This argument may seem oversimplified. Wealthy people may have the ability to mitigate risk more easily by, for example, buying bottled water. Beck argues that the distribution of this sort of risk is the result of knowledge, rather than wealth. The two-wealth and access to knowledge or relevant information- are however not unrelated.

As Beck would argue, in COVID-19 times, no one is free from risk. But as increasingly evident the ability to isolate, work from home, home-school your children, stockpile your shelves, access healthcare, and financially (and psychologically) put your life back together after the pandemic is class, gender, race, age, and geography dependent[v]. The claim that we are all in the same boat perhaps needs rephrasing to the claim that indeed we are all in the same storm but our boats are different.

This pandemic has been an eye-opener to rethink human relationships with nature and the model of development that we have pursued. As Beck writes, ‘the existence of world risk society is denied, the more easily it can become a reality. The ignorance of the globalization of risk increases the globalization of risk’ (ibid: 330).

Nabajyoti Saikia is a PhD research scholar in the Department of Sociology, Dibrugarh University.

-----

[i] Beck, Ulrich. (1999). World Risk Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

[ii] Beck, Ulrich. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Sage Publications.

[iii]https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4095470/mod_resource/content/0/Beck--WorldRisk.pdf, accessed on 5th July 2020.

[iv] https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4095470/mod_resource/content/0/Beck--WorldRisk.pdf, accessed on 5th July 2020.

[v] https://www.wilpf.org/covid-19-what-has-covid-19-taught-us-about-neoliberalism/, accessed on 6th July 2020.

***

Comments

Post a Comment